The Heart-Wrenching Truth about Residential Schools

The Heart-Wrenching Truth about Residential Schools

The Heart-Wrenching Truth About Residential Schools

By: Angélica Boucher

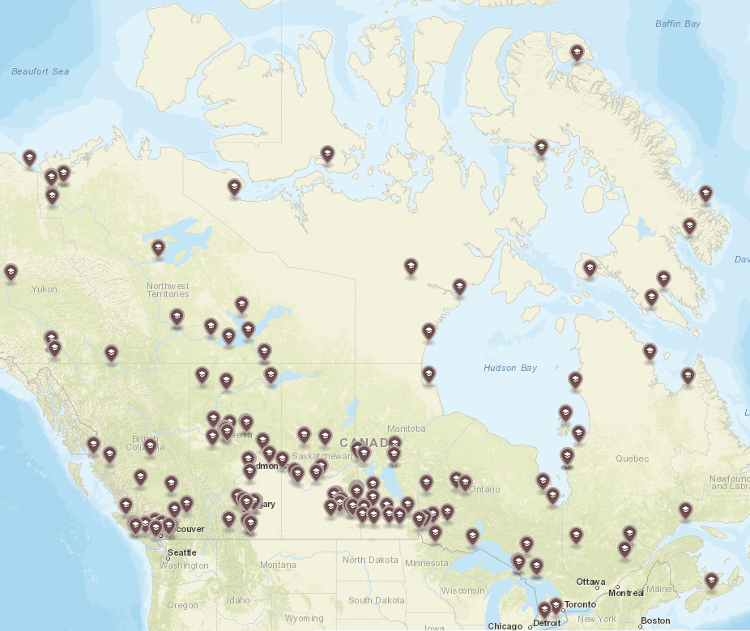

(Photo from National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

Content Warning: This blog contains information that might be upsetting for some readers. The topic of residential schools is discussed in detail alongside personal accounts.

To begin, I would like to acknowledge that I am not a residential school survivor and thankfully, none of my Indigenous ancestors were forced to attend residential schools. Therefore, it is not my place to recount the nightmarish experiences that children underwent while at residential school. What I may share though, are the facts and the words of those who are survivors.

- · More than 150 000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were forced to attend

- · 150 residential schools throughout Canada

- · 25 residential schools in Alberta

- · More than 150 years of operation

- · 80 000 residential school survivors alive today

- · More than 6000 children died in residential schools

For the majority of Canadians, these facts have been hard to acknowledge. That is, until the bodies of 215 children were uncovered on the grounds of former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Indigenous peoples already knew or had strong suspicions that the bodies of their fellow classmates, siblings, friends, and children were there. As Elder Ekti Margaret Cardinal stated during one of our conversations, “we have been telling people [about the abuse] for years, but they didn’t listen.”

Despite the many accounts of survivors sharing similar experiences of atrocities committed in residential school, Canada needed the bones of children to start the acknowledgment process. Even then, Richard (Steinhauer) Swaren, a Knowledge Keeper from Saddle Lake First Nation, explains that, “when the first 215 children were discovered, it made media all over the world. We are at 7000 plus now and it is already old news.”

Ekti invites us to reflect on “how wrong is it that it was kept silent?” We need to break the nation-wide silence that has persisted.

What was the purpose of residential schools?

As a child, Elder and tipi maker Ekti Margaret Cardinal was forced to attend Blue Quills Indian Residential School for ten years. When asked about her experience in boarding school, Ekti commented that “all the focus was to get rid of the Indian in you.”

The purpose was to assimilate and legally extinguish Indigenous peoples. Although residential schools started as early as 1831, government funded industrial schools (or residential schools) started later in the 1880s. The last federally funded residential school closed in 1996. An important influence on the funding of residential schools was a report written by Nicholas Flood Davin in 1879, who’s report was commissioned by Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald. Based on the United States industrial school model, Davin expressed the need for such school in order to “civilize” Indigenous peoples. Of note, in the Davin report, it is written that “the aim of education must be to destroy the Indian.” The intent cannot be clearer than that statement. To read the Davin Report, see the reference list below.

From day one, abuse was present, as children were ripped from their home, their families, their culture, and their language, often without warning. Immediately, children were experiencing emotional neglect, and often, would be victim to various other forms of abuse (i.e., verbal, sexual, physical). Residential schools were generally in poor conditions, as they were underfunded, overcrowded, and staffed with underqualified educators. And be assured, the government knew about these awful conditions due to written reports, such as the ones written by Dr. Peter Bryce in 1909 and 1927. However, the government deliberately chose to ignore them.

As for the quality of education, Ekti explained that before the 1950s, which was when her mother had attended boarding school, children would get at most three hours of education in a day. The rest of the day was spent doing work and chores. Therefore, the purpose was not to provide Indigenous children with an adequate and/or similar education to that of other children in Canada. Clearly, residential schools had more resemblance to workhouses or assimilation camps than schools.

If you would like to learn more about Ekti’s boarding school experience, click here[BB2] to read her interview with the Native Women’s Association of Canada Magazine KCI-NWESQ.

Did the loss end there?

Over the past few months, I have had the chance to converse with many Indigenous community members throughout Alberta. A common theme that tends to surface in our discussions is this sense of fear. Understandably so, as the loss and abuse of Indigenous children did not end or begin with the residential schools. As Richard expressed, “[Colonialism] accomplished its goal through Indian Residential School, through Indian Day School, and continues to do so through all its other systems, including Child and Family Services, the prison system, the legal system, and the medical system.”

Darren Weaselchild, a Knowledge Keeper from Siksika First Nation describes Child and Family Services as the new Indian Residential School System. He explains that when children are taken from Indigenous families, they are typically put into non-Indigenous homes where they must conform to mainstream society and do not get the opportunity to know their roots. Darren adds a heartfelt message: “we would like our children to be raised with their culture, raised with their braids, and raised with their elders.”

“As a people, we are like the buffalo”

The National Truth and Reconciliation Day is a time to commemorate the children that survived the Indian Residential School System and those who did not.

As Ekti says, “we need to think of all the people that died;” we must remember them. However, I would argue that it is equally as important to reflect on the pure strength that Indigenous peoples had to demonstrate in order to withstand the continuous effort to eradicate them.

During our conversation, Ekti recounted that “in boarding school, what really supported me, was prayer. You had to believe that things are going to happen, that you are going to survive. I had to believe that I was going to survive this and not let go.” As a form of punishment for “doing something Indigenous,” Ekti was forced to stand in front of a pillar wall for up to three hours. She explained that in those moments, in her mind, she would travel back to her grandparents, to her parents, or to a nice summer fishing. Ekti explained that “if you only think of negative things, then they have control of you.” She did not let that happen, she thought of happy moments, and that helped her survive. Stories of strength, such as Ekti’s, also need to be remembered and honoured, as it is that strength and bravery that allowed Indigenous peoples to exist today.

I would like to end this blog on a beautiful teaching that was generously shared with me by Darren Weaselchild. “There’s a story of the buffalo herd. The buffalo herd will not sit and wait when there’s a storm. Instead, they would go and push through it until they got to the other side. As a people, we are like the buffalo.”

We thank the Elders who have shared their knowledge and experiences with us for this interview.

Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre. (n.d.). Davin Report. The University of British Columbia. https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/objects/9427

Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre. (n.d.). Indian Residential School. The University of British Columbia. https://irshdc.ubc.ca/learn/indian-residential-schools/

Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre. (n.d.). The story of a national crime: being an appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada. The University of British Columbia. https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/objects/9434

KCI-NIWESQ. (2021, August). Three Residential School Survivors and the Brutality that Shaped their Lives. Native Women’s Association of Canada Magazine, 1(5), 9-13. https://issuu.com/kci-niwesq/docs/kci-niwesq-issue_5-august_2021/2

Marshall, T., & Gallant, D. (2012, October 10). Residential Schools in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

CONTACT

Imagine Institute For Learning

#624, 7 Sir Winston Churchill Square NW,

780-428-9465

Toll free: 1-877-652-1524

© Copyright 2023 | Imagine Institute for Learning